Two weeks ago, I travelled to Oslo for the first annual meeting of ACHS Norway, a national chapter of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies. It was an opportunity for me to find out more about critical heritage studies in Norway and to spread the word about the newly launched ACHS Early Career Researcher Network. The theme for the day was “Hva er kritisk kulturarvforskning i Norge?” (What is critical heritage studies in Norway?) and while this was discussed throughout the event, arguably the more fundamental question of “what is critical heritage studies” took centre stage.

The day began with short introductions from the ACHS-N board:

Gørill Nilsen, from the University of Tromsø, began by sharing her personal heritage, identifying as Norwegian, Sami and Kven, and how this influences her research. She made the point that she, like many others, has been engaged with critical heritage studies for a long time, despite only recently hearing of the term. She touched on issues relating to Sami archaeology and her frustration with maps depicting Viking lands stopping at Trondheim before ending with a challenge for critical heritage studies in Norway to more often look northward.

Terje Brattli, from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), warned us of becoming too concerned with “the Authorised Heritage Discourse” and the conflict between experts and non-experts, highlighting that there are many other conflicts and more nuanced power-dynamics worth investigating. He came with a challenge to look more at practice and less at predefined positions, and to approach knowledge and knowledge production in new ways. He also raised the issue of difficult or “dark” heritage, emphasising that the removal of the NS Monument could in some ways be compared to the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas. He suggested that critical heritage researchers should look at unusual contrasts and comparisons.

Marit Johansson, from the University College of Southeast Norway, shared her hope that ACHS-N could become a lasting meeting point for heritage researchers and those who work in public heritage organisations in Norway. She outlined how this could lead to the development of new avenues for research and a greater awareness of the types of research that are needed. She also challenged ACHS-N to make critical heritage studies more visible publicly.

Nanna Løkka, from Telemark Research Institute, began with her hope that bringing researchers and public heritage organisations together through ACHS-N might allow public organisations to become less defensive and recognise the importance of critical perspectives. She counterbalanced this through a reminder that we must also critical of critical perspectives. She called for more nuance with regard to the criticism of experts in light of growing radical populism. She suggested that it is boring to exclusively be critical; we must be critical and creative, critical and constructive.

Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen (@TorgrimG), from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU), suggested that ACHS-N is more than a smaller ACHS; it is an opportunity to discuss issues at a different scale in a forum that is more homelike. He invited us to consider what Norway has to offer the world. What is heritage’s cheese slicer or paperclip (two of Norway’s greatest inventions)? He emphasised that foreigners are often interested in Norwegian concepts like “dugnad“, the Nordic social democracy and Norwegian perspectives on Brexit. In Norway, the idea of an entrepreneur being involved in a public park is strange, but he suggested it wouldn’t be in the USA. He ended by asking how these things influence heritage policy and practice – what does Norway have to offer critical heritage studies internationally?

Following these short introductions, Herdis Hølleland (@HHolleland), also from NIKU, gave a presentation on critical heritage studies in Norway. As part of her preparation for the presentation she had surveyed the ACHS-N membership in order to find out more about their backgrounds, research interests, affiliations and understandings of “critical heritage”. She made the point that everyone seems to think critical heritage studies is about power and politics, but none of her respondents had ever worked in politics. She also highlighted that for critical heritage, it is the subject, not the methods, that define the field – yet the subject (heritage or critical heritage) is rarely defined. This talk set the scene for the discussions of what critical heritage studies is and what ACHS-N should be about that continued throughout the day.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

It was then time for lunch and the AGM itself, where Gørill Nilsen raised the issue of the name of ACHS-N. ACHS-N has been promoted as the Norwegian Chapter, but she suggested that it should instead be the Chapter in Norway, as “Norwegian” is a more exclusive term than “Norway”. Given the centrality of postcolonial research and indigenous rights to critical heritage studies, it was suggested that “Norway” (outlining a territory) should replace the use of “Norwegian” (outlining a language and culture), thereby avoiding the exclusion of Sami, Kven and other minority cultures in Norway.

The proposed purpose statement for ACHS-N also prompted discussion (found under point 7 at the end of this page). The term “kritisk kulturarvforskning” (critical heritage studies) was used twice in the statement. One suggestion was that “kritisk” should be dropped, prompting a discussion of how invested we were in the “critical” in critical heritage studies and what “critical” means in a heritage context. This reminded me of a similar discussion I had heard took place in the WAC (World Archaeological Congress) mailing list last year about whether or not archaeology is political. WAC is an organisation that was founded as overtly political, in reaction to other international archaeological organisations that wanted to keep politics out of archaeology. Similarly, here I was at the annual meeting of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies in Norway, participating in a discussion about whether or not the emphasis on critical is significant or not.

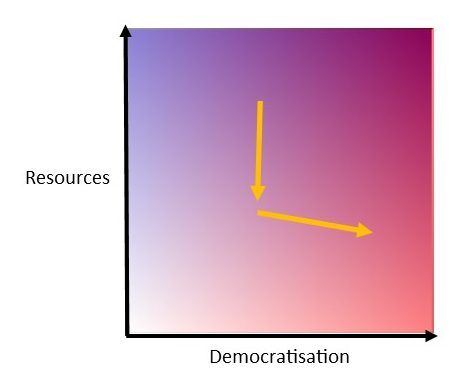

In this context I think it is important to understand that heritage studies has emerged from a range of different academic disciplines, professions and specialisms. I think there are two problems here. The first is that there is no international organisation for heritage studies and few national fora that bring heritage researchers and practitioners together. The second is that proponents of critical heritage studies have not been clear enough about what “critical” actually means in a heritage context.* Critical heritage studies was coined (and the ACHS formed) as a reaction to heritage research and practice predominantly being concerned with the what and the how of heritage, rather than the why and so what. Nevertheless, the success of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies has propelled it into a position of being THE international organisation for heritage studies. I sensed this quite clearly at ACHS 2016 in Montreal, which, while a wonderful conference, seemed to want to be both THE critical heritage conference and THE heritage conference all at once. Heritage researchers and practitioners are the most obvious potential members for the new Association, but their majority also represents what critical heritage studies is a reaction against. Significantly, they are also an audience in need of national and international fora that bring their disparate members together – something ACHS and its various networks and chapters could seem to offer. In this context, the questioning of the importance of “critical” by new (potential) members at the ACHS-N chapter in Norway is perhaps not surprising.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

After the AGM, proper, came the presentation that I found the most powerful. Tor Einar Fagerland, Head of the Department of Historical Studies at NTNU, spoke about his work with the Workers’ Youth League (AUF) following the terrorist attacks in Norway on the 22 of July, 2011, and his research on July 22 and the Negotiation of Memory. Four articles about his work were published in the Norwegian national newspaper, Aftenposten, three of which I was able to find through a quick search (published 15 July 2015, 14 July 2016 and 9 Feb 2017). He spoke about spending time with the AUF group and their families and the work he did with them, both on Utøya and in Oslo. He told us how when the Americans brought in to consult on the project had asked “what are the traditions in Norway of dealing with these kinds of events”, the question was met with a stony silence – there are no traditions. Fagerland highlighted that the building on the island where some of the young men and women were shot and killed was both a house of death and a house of survival. 7 survived inside, crammed into a toilet cubicle.

Unlike most buildings conservation, which emphasises retaining exteriors, dialogue highlighted that what was important about the building on Utøya was the interior. The building has now been transformed into a learning centre. Most of the centre is new, including 69 wooden posts representing the individuals who lost their lives that day, but it incorporates parts of the original structure where 13 died and 7 survived in the toilet cubicle.

Fagerland also discussed the work of creating the 22 July Centre in Oslo and the input from US partners. He recalled being advised that you can do whatever you want, as long as you begin by telling what happened. This is what the 22 July Centre does. I was able to make time for a short visit there, following the AGM, before they closed for the day. The Centre is in spaces damaged by the bomb blast outside the government offices in Oslo and the displays are simple and frank – featuring text messages from the day. Fagerland mentioned that there was never any doubt what Ground Zero would be used for following the attacks on the World Trade Centre, but unlike the 9/11 Memorial Museum, the debates about whether or not there should be a 22 July Centre continue. Is the Centre important? For whom? It has been suggested that the Centre will be removed when the government building is renovated, prompting a public debate in national media – a debate in which no museum professionals, humanists, or cultural research centres like NIKU have taken part in. Fagerland emphasised that he was not highlighting this as an accusation, but as a question. If we think we our research is so important to society, why do we stay silent when society debates dark heritage?

Other presentations followed this, Atle Omland, from the Directorate for Cultural Heritage, spoke about critical heritage studies’ need for pathos and Gro Birgit Ween, from the University of Oslo, discussed her exciting interdisciplinary Housing Heritage project – but I think I want to end on Norway’s dark heritage and the lack of “expert” engagement with the public debate around it. I don’t know why the “experts” were silent. I don’t know if it was because they felt they didn’t have the answers. I wish we would engage publicly when there are no answers – not with inflated egos and false bravado in cases where we don’t have the answers and others do – but when our expertise may be useful without being authoritative. From my, ever hopelessly idealistic perceptive, this is where the potential power of critical heritage studies lies.

*My understanding of the “critical” in critical heritage studies is an expression of alignment with Critical Theory, which posits that current reality and practice is not necessary or inevitable, but the result of power and ideology. It is in this tradition that Laurajane Smith wrote about an “authorised heritage discourse” (see cultural hegemony) which outlines how certain ways of seeing and using heritage have become normalised. Critical heritage studies, then, is about how heritage is used in society, what it does socially, politically and economically, and about uncovering how heritage practice and theory marginalises, excludes and reinforces existing power-dynamics through supposedly neutral processes and concepts. It is not just about criticising, but critique is a significant feature. My take on “critical” is that it encompasses both “constructive” and “creative” – it is about identifying that the present is not neutral or necessary, highlighting that things could be different and about causing change.

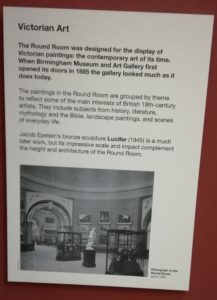

The open evening was amazing. It began with welcome drinks and DJ Chakraman in the Round Room, which according to a panel, ‘looked much as it does today’ when it opened in 1885. I’m sure it looks much like it did most days, and it did earlier in the afternoon when I came to see the exhibition, but that evening it was decidedly different. The music. The people. The energy. It was a very different space. And it hinted at what entry spaces like the Round Room could be if museums were willing to look beyond their tired tropes and tones. The demographic difference between then and only a few hours previously was remarkable and should speak loud and clear to the fundamental shift that is required to attract “hard to reach” audiences.

The open evening was amazing. It began with welcome drinks and DJ Chakraman in the Round Room, which according to a panel, ‘looked much as it does today’ when it opened in 1885. I’m sure it looks much like it did most days, and it did earlier in the afternoon when I came to see the exhibition, but that evening it was decidedly different. The music. The people. The energy. It was a very different space. And it hinted at what entry spaces like the Round Room could be if museums were willing to look beyond their tired tropes and tones. The demographic difference between then and only a few hours previously was remarkable and should speak loud and clear to the fundamental shift that is required to attract “hard to reach” audiences.