In my last post I said I would write more about connecting reflections on my research and teaching. This is something I have thought quite a lot about this spring and summer.

In April, I was asked to teach on the Heritage Practice field school again. Last year, Meghan Dennis (@gingerygamer & @archaeoethics) and I worked with Sara Perry (@ArchaeologistSP) and a group of 1st year undergraduates to create an audio guide and paper-leaflet for Breary Banks in the Nidderdale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The students’ work is still available on the project blog – it’s definitely worth a look. This year, Meghan and I were asked to take on more responsibility for the field school; the compromise was that we would be allowed to shape the work with this year’s project partner – Malton Museum – according to our own research interests. The museum had already expressed an interest in a digital game and given Meghan’s research into video games and ethics it was a perfect fit. With regard to my own research, the connection was that the museum is run by volunteers and that making a game would provide an opportunity to explore co-design from another angle.

Leading up to the course, I was wrestling with how we could use co-design in the field school. In the end I settled for teaching user-centred design instead, as we would only be spending a few hours with the museum volunteers – it wouldn’t really be possible to design together. Meghan suggested that maybe it still was co-design, but that the students were our co-designers instead of the volunteers at the museum. At the time, I wasn’t quite satisfied with this perspective, but she was right, of course, and I want to share some reflections around this experience here.

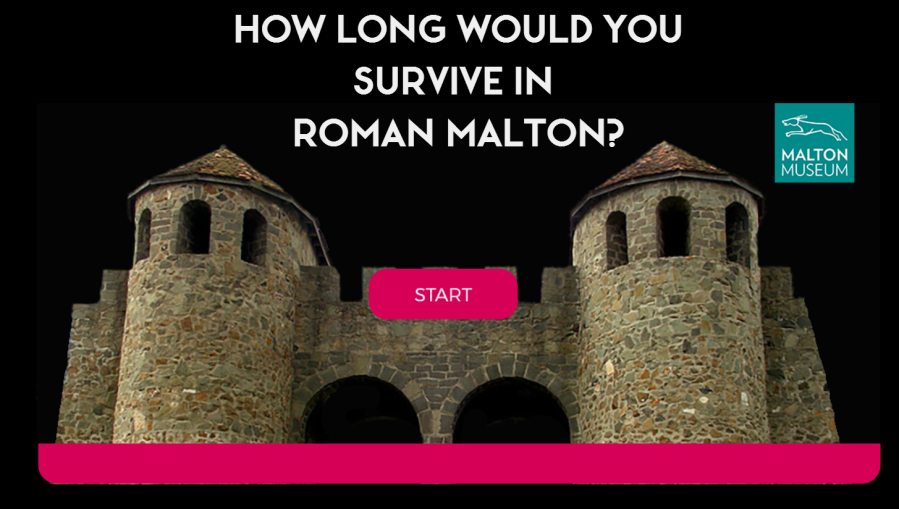

The design and production process can absolutely be understood as co-design in that while we wanted the students to make the decisions and do the work. That said, we were working with students who had *no* experience with game design and limited digital skills. The students were responsible for planning and executing the design and production process, but we had to make that possible – facilitating this in practice was a classic case of negotiating #hexpertise. As instructors, we had to determine what we should do for the students and what we should make them do themselves, both in order to maximise learning and to produce a product we were satisfied with. I think it’s fair to say it was a great learning experience for everyone involved. You can read the students’ reflections on the process, as well as their final report on their project blog. The game is available there too – how long would you survive in Roman Malton?

In terms of comparing the processes of co-designing for my research and co-designing as part of my teaching, the most obvious difference is how much time we spent together. While we only had two full weeks to design and produce the game, we spent 24 hours together each of those weeks. That is a lot of intense contact time. There are obviously a host of other differences between working with students and working with community partners, but the difference in contact time matters. How can you truly design together without enough time. Taking this idea further, the students spent all that time with us because it’s their job to. They are full-time students – my community partners are not. Their commitment to their local heritage is voluntary and their work with me is just one small part of that. One of the many issues wrapped up in #hexpertise is that of having someone paid to work full-time collaborating with someone who is participating on a voluntary basis alongside their other commitments. As a result, expertise is just one dimension of #hexpertise. This doesn’t mean that my work with my community partners isn’t co-design – it just highlights that all co-design projects are different and that questions of #hexpertise must be negotiated on a case-by-case basis. There may be common underlying principles – these are what I’m trying to get at in my research – but the way those principles are enacted in practice has to vary.

To design and produce the game, I introduced the students to user-centred design by sharing an experience from my MSc degree that I sometimes describe as producing a solution that nobody wanted. The first principle of user-centred design is to create something that your user wants. The person you are designing for should want to use what you have created – you’re facing an uphill battle if you create something that you then have to convince people they should want to use. I performed a mock design exercise with them to help them plan exercises they could use with the museum volunteers, and I was there while they were planning, offering advice and being available as a resource for them to use. Later, when it came to actually producing the game, Tara Copplestone (@Gamingarchaeo), our resident game-design genius and Twine extraordinaire, provided the necessary frameworks for our students to be able to produce their game. The students would not have been able to create everything from scratch in the time available, so Tara provided what was necessary and was on hand to help. The students designed and made their game, but without the support available, that would not have been possible. These decisions about the support to provide and how to provide it are complex decisions – and it’s not just a question of providing or holding back in order to create the perfect challenge. That certainly is not how I work with my community partners. They are questions of agency and ownership and they are questions of expertise.

The kind of collaborative work I love is when people with different sets of expertise work together to create something that none of the individuals could have created on their own. I really don’t like the model of “experts” and “non-experts” working together, where “experts” are worried “non-experts” aren’t doing it right and “non-experts” get to be involved by necessity or as an act of charity. In a university setting with students and instructors, my ideal model for collaboration is warped slightly, but I firmly believe that we could not have created the game we made without the students.

In terms of my work with my community partners, I absolutely see it as individuals with different sets of expertise working together. But we’re still identifying our own expertise and figuring out how to best work together for everyone’s benefit. The experience of working with my students has changed my perspective and my expectations of working with my community partners. As I keep co-designing, I keep learning – hopefully for the benefit of everyone I work with!