Those of you who know me well may remember that when I began my PhD, I was eager to talk about austerity as an opportunity, not just a threat. I wanted to move beyond merely protesting against austerity and do something productive in (or despite of) austerity.

For decades, more progressive heritage professionals and academics have been promoting the idea that everyone has a right to identify their own heritage and be involved in caring for it, but little has changed in practice. I thought maybe the loss of professional capacity caused by austerity could be used to force change. If we want local people to care for their own heritage, according to their own values and priorities, maybe we need professionals to leave. Maybe, I thought, what the heritage sector needs, is a bit of a crisis.

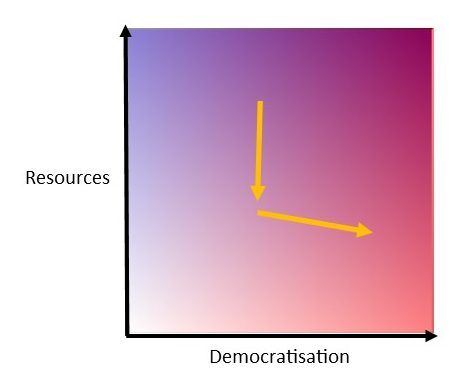

My current thinking is that there are two main drivers for including volunteers in caring for heritage. One is to save money (it’s cheaper to not pay a volunteer than to pay a professional). Another is this progressive agenda of increased local, non-professional agency (let’s call it democratisation). One of the questions I asked myself early on was whether these drivers are mutually exclusive: is it possible to both save money and democratise? A related question is whether it is possible to use volunteers to save money without exploiting them. One of my focus group participants told me categorically NO. Putting on good volunteering opportunities takes effort and requires resources. If we’re looking to volunteers to boost our capacity and balance our books, we’re exploiting volunteers and devaluing professional labour. So what do we do when we’re faced with budget cuts AND we want to democratise? In my mind, the only way we can do this is by letting go. I realise this is not possible for everyone, but I wonder whether it is possible more often than we think.

Let’s suggest for now that democratisation is positive. If so, the ideal situation is the purple area in the top right of the figure above. My observation going into the PhD was that we were never there, even before austerity, and I didn’t think it looked like we were on our way there either (at least not fast enough!). I thought a loss of resources might drop us down into the redder area and drive us to the right out of necessity. This might involve letting go of some of the things we think of as necessary and diverting our attention to supporting people according to their priorities. My current observations are that this doesn’t seem to be happening. There are other ways to maintain capacity and uphold existing priorities despite a loss of resources – like asking people to work for you for free.

In this regard (as so many others) trends in the heritage sector mirror those of society as a whole. Paid jobs are transformed into unpaid (volunteer) positions, dressed up in the language of democratisation and celebrated as victories for volunteering. For those who can afford to work for free, this may not be a problem. Austerity will always disproportionately affect those less well off. This brings me to the NCVO General Election Manifesto that says it should be ‘easier for charities and volunteers to support public services’ and the Guardian’s “UK desperately needs new volunteers to fill yawning gaps in public services“. Do we really want more volunteering in public services?

- Less funding doesn’t magically clear the way for the masses who have yearned to transform local services for free.

- Less funding doesn’t simply provide rich and rewarding opportunities for volunteers.

- Local (voluntary) input may improve public services (heritage included), but this input must be resourced so everyone can participate, and facilitated so participating is meaningful.

I don’t know that much about most public service provision, but specifically with regard to heritage:

- I think change is needed.

- I think democratisation is positive.

- I think this must involve some letting go.

- I think a loss of resources can prompt beneficial discussions about priorities.

But those discussions do not create a willingness to democratise – unless that willingness is already there, any increase in volunteering is more likely to resemble exploitation than democratisation. So finally:

- I still think we need to reassess and renegotiate roles, responsibilities and priorities.

- We don’t need austerity to do this.

- Unpaid jobs should not be celebrated.

- Purple will always be better than red.