Last Friday I was at the Natural History Museum (@NHM_London) for an event on citizen science and crowdsourcing. It was called “Connecting with the Crowd” – you can look up tweets using #crowdsourcingNHM. I don’t want to spend too much time talking about what citizen science and crowdsourcing are. If you’re curious about citizen science, check out the Zooniverse where you can participate in “people powered” research. While crowdsourcing is used for-profit in big business, let’s for now go along with the idea that crowdsourcing in heritage contexts can be understood as digital volunteering. You’re volunteering, but it’s online instead of at your local museum or library. You may be transcribing handwritten text, tagging images or video clips.

Crowdsourcing can be ethically murky, as many projects involve farming out repetitive tasks on a massive scale that institutions aren’t able to address professionally. I was curious to see whether the speakers at “Connecting with the Crowd” would address this. I was disappointed to find that they didn’t really, but the projects mentioned and issues raised clarified a few things for me in my mind.

Most heritage crowdsourcing projects report “super-users” and “long tails”. In most projects, the vast majority of contributors make a small number of contributions, while a small core of “super-users” complete tens- or hundreds- of thousands tasks. There was a presentation addressing this directly, offering techniques to try to keep contributors engaged by sending reminder emails etc. when they had been inactive for a while. Sitting there listening to this I couldn’t help but think: surely most people don’t come back because while participating in “real” research may sound like a cool idea, the reality of performing these repetitive tasks is not that compelling.

There was a presentation by the creators of the Zooniverse, who discussed a success story, where the discussion forum used by their users had led to contributors becoming co-authors in a professional publication using the crowdsourced data. This is a cool story. Those users really got to actively contribute to, and be involved in, cutting edge research – but the majority still just get to do grunt work, however colourful. The whole idea of crowdsourcing is to make volunteering efficient and to require as little of the professional as possible.

By contrast, the Visiteering programme at the Natural History Museum let’s you volunteer in the museum for a day, working on a real project together with a real scientist. Through the day, it was highlighted that what makes citizen science participants come back is interaction with real scientists – this is the main selling point for the visiteering scheme.

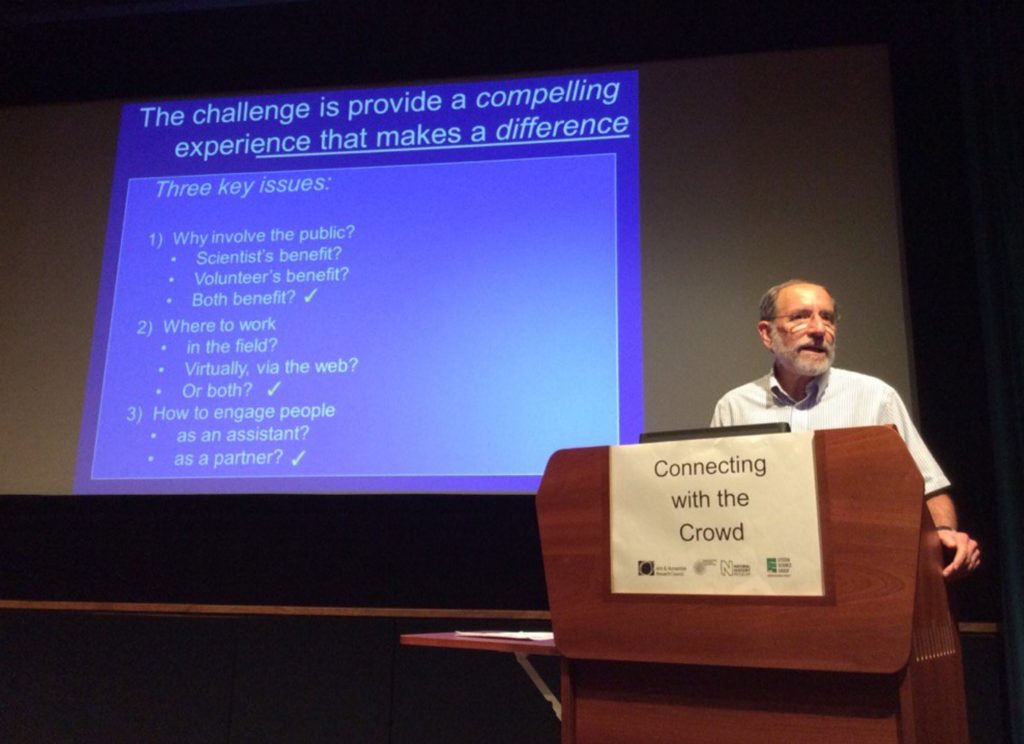

The closing keynote was by Dan Rubenstein on his citizen science work in Kenya. Before discussing his project, he highlighted the need to provide compelling experiences that make a difference. While the whole room agreed with his three key issues highlighted in the image below, few if any of the other projects presented at the conference live up to these ideals. He pays his participants a living wage, gives data collectors ownership of their data and includes them in data analysis. He doesn’t involve Kenyan’s in his work with the Grevvy Zebras because it saves him money, but because local people have the necessary local knowledge to do the work in their native landscape.

Most citizen science and crowdsourcing projects are designed to provide exactly what the researcher needs, through an experience they hope someone will find compelling enough to do for free. This is obvious if you consider how these projects and websites are designed.

You wouldn’t invite someone to volunteer at your museum without giving them any face-to-face time with a member of staff. You wouldn’t have them follow signs to a large room with a huge stack of papers for them to transcribe with just a post-it note on the table that says “thanks” – and hope that someone would leap at the opportunity and keep coming back, day after day.

Using web-technology for volunteering makes it easy to keep volunteers at arms length and not worry too much about who they are, what they want and whether or not they find their role worthwhile – as long as someone else is there to pick up the work when they’ve had enough.

If your goal is to work with volunteers as partners for all to truly benefit, this will be obvious in how you design volunteer experiences – whether online or in person. Providing meaningful experiences that make a difference isn’t simple and it’s unlikely to be efficient or cost-effective. Engagement activities shouldn’t be about saving money – if they are, how is that not exploitative?