The co-design project that was the driving force behind this blog came to a slow, somewhat unsatisfying end some time ago. That, and the fact that I have been overwhelmed with writing up my thesis while applying for post-PhD work for the past six months, goes some way to explain the length of time since my last post. I will at the very least write one blog post about the end of the co-design project at some point, but for now I want to focus on the thinking I have been doing about “what’s next” – which is all connected to Birmingham Museums’ exhibition “The Past is Now“, which I have been putting off writing about for ages.

It began with Sarah May’s (@Sarah_May1) tweet last summer about how the results of the 2014 YouGov poll on “Pride in the Empire” and “Empire’s Legacy” (brought back up by YouGov in a tweet last July) are ‘a shocking failure of the heritage sector. We peddle fantasies of glory that directly contribute to contemporary problems.’ It initiated a process of thinking about how I, as a critical heritage researcher, could address how “toxic whiteness” is created and perpetuated through heritage practice. It was while in this frame of mind that I came across the exhibition and one of it’s “co-curators”, Mariam Khan (@helloiammariam), on Twitter – and promised I would try to go see it.

In the end, I was able attend most of the open evening on the 8th of December and to have a proper look before the space filled up earlier in the afternoon. The exhibition was brilliant. Not only did it present a frank perspective on Birmingham’s colonial past, it foregrounded that this is not all in the past – the past is now. It also commented on the past and present function of the museum within which it was housed. The contrast between “The Past is Now” and the rest of the museum is stark – and invites the visitor to consider museums as active agents in pasts that are present.

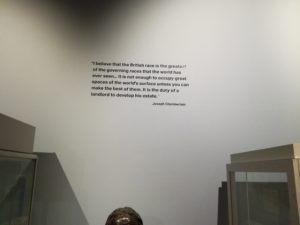

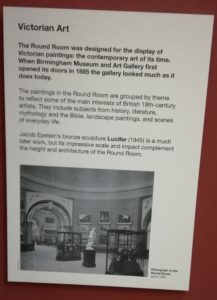

The open evening was amazing. It began with welcome drinks and DJ Chakraman in the Round Room, which according to a panel, ‘looked much as it does today’ when it opened in 1885. I’m sure it looks much like it did most days, and it did earlier in the afternoon when I came to see the exhibition, but that evening it was decidedly different. The music. The people. The energy. It was a very different space. And it hinted at what entry spaces like the Round Room could be if museums were willing to look beyond their tired tropes and tones. The demographic difference between then and only a few hours previously was remarkable and should speak loud and clear to the fundamental shift that is required to attract “hard to reach” audiences.

The open evening was amazing. It began with welcome drinks and DJ Chakraman in the Round Room, which according to a panel, ‘looked much as it does today’ when it opened in 1885. I’m sure it looks much like it did most days, and it did earlier in the afternoon when I came to see the exhibition, but that evening it was decidedly different. The music. The people. The energy. It was a very different space. And it hinted at what entry spaces like the Round Room could be if museums were willing to look beyond their tired tropes and tones. The demographic difference between then and only a few hours previously was remarkable and should speak loud and clear to the fundamental shift that is required to attract “hard to reach” audiences.

Sumaya Kassim (@SFKassim), one of the six supremely talented “co-curators”, wrote about the exhibition and her experience as a co-curator for Media Diversified last autumn in a piece titled “The museum will not be decolonised“. The piece explicitly expands the exhibition’s critique of the sector in multiple ways. It is a MUST READ. Go read it now before you read the rest of this.

Now that you’ve read it, I especially want to highlight these two paragraphs:

‘Rather than place the onus on people of colour – either as facilitators or as an audience for the museum – we need to flip the narrative and ask how the museum can facilitate the decolonial process for its majority white audience in a way that does not continue to exploit people of colour. Key to this is accepting that the museum needs us; we do not need the museum. Institutions need to stop considering giving access to BAME people’s own cultures something they should be grateful for, and they should definitely ensure that ‘focus groups’ and visiting curators are remunerated adequately for their work.

This came to a head at the last meeting. We raised these issues – about emotional labour, about not receiving adequate pay for the work we were doing, and about the fact certain key decisions were made without us – and explained that the co-curation process betrayed a fundamental lack of understanding of what decoloniality is and who it is for. We argued that words and systems that hide exploitative practices such as ‘volunteering’, ‘zero-hour contracts’, and ‘diversity’ have no place in a decolonial project. Too often people of colour are rolled in to provide natural resources – our bodies and our “decolonial” thoughts – which are exploited, and then discarded. The human cost, the emotional labour, are seen as worthy sacrifices in the name of an exhibition which can be celebrated as a successful attempt by the museum at “inclusion” and “decolonising”, as a marker that it – and, indeed, Britain – is dealing with its past.‘

Since seeing the exhibition and reading Sumaya Kassim’s piece, I’ve tried to educate myself on issues of race in the UK. I’d highly recommend Reni Eddo Lodge’s Why I’m no Longer Talking to White People about Race and Afua Hirsch’s Brit(ish) as places to start. Both books are current, powerful, engaging and informative page-turners. Neither is explicitly about cultural heritage, but both clearly communicate the message that The Past Is Now and that the narratives of the past that are perpetuated through heritage practice have serious personal and societal consequences. This was brought to the forefront of my mind today as Afua Hirsch tweeted the tweet below:

After no of recent arguments made it clear to me prominent Brits still sympathise more w plantation owners than revolutionary slaves, I can safely say UK is SO far from this >> Denmark Gets Statue of a ‘Rebel Queen’ Who Led Fiery Revolt Against Colonialism https://t.co/wAZesWBG03

— Afua Hirsch (@afuahirsch) April 2, 2018

The linked article ends with the following note:

‘In a speech last year, the Danish prime minister, Lars Lokke Rasmussen, expressed regret for his country’s past in the slave trade – but he stopped short of an apology. “Many of Copenhagen’s beautiful old houses were erected with money made on the toil and exploitation on the other side of the planet, he said. “It’s not a proud part of Denmark’s history. It’s shameful and luckily of the past.”‘

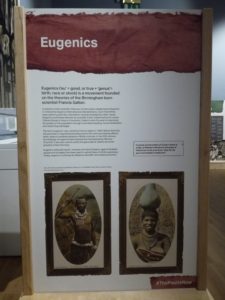

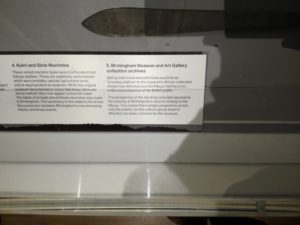

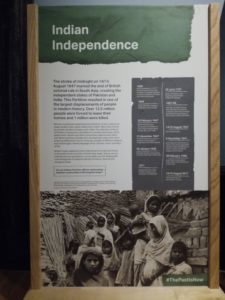

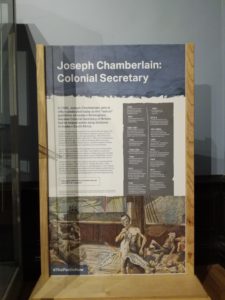

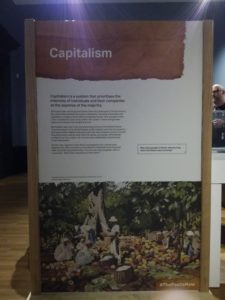

Only it’s not, of course. I’ll leave you with some pictures of panels from “The Past Is Now” and Sumaya Kassim’s challenge not to shirk the responsibility of addressing enduring toxic legacies of Whiteness.